As I’ve previously noted, one of the good things about my current period of unemployment is that I’ve been able to take advantage of access to a couple practice instruments and really dive into learning a bunch of repertoire solely for myself, rather than under the stress of preparing for a competition or high-pressure recital. More often than not, I’ve noticed that I leave my practice sessions with higher spirits and the sense of having accomplished something — a rarity in other parts of what has become a monotonous daily routine (working part-time delivering groceries, lazing around, and trying my best to keep my body and brain relatively active)!

Recently, I just put finishing touches on Bach’s Trio Sonata No. 1 in E flat major- ironically the final one I’ve learned of the six in the set. Being able now to pronounce that I’ve officially learnt all 18 of these movements feels great! It’s been gratifying to tie up other “loose ends” in my repertoire, like finishing Franck’s Trois Pièces and working through other collections, too. It’s still bittersweet, though, to finish the Trio Sonatas (BWV 525-530), and it’s given me a chance to look back at my journey with each one:

I started by learning the slow middle movement of Trio No. 2, which I had the opportunity to perform in my capacity as Organ Scholar at the Saint Thomas Girl Course, when I was still in high school. I played it on the Loening-Hancock Organ in the gallery before one of our weekday evensongs, and unfortunately I seem to remember nerves getting the best of me for much of it- oh well! After that, I worked with my high school organ teacher to learn all of Trio No. 4. The sixth trio was a project during my first year of undergraduate studies at Eastman with Professor Porter; it provided a much-needed wake-up call with regards to touch and technique. At this point I didn’t feel quite so warmly towards Bach’s famous pedagogical tool for his son as I do now — wisdom comes with age and experience! After a respite of a few years, I jumped back in to the world of trio sonatas during my year as Organ Scholar in Truro with No. 3 - I remember realizing how unique an experience it probably is to learn a trio sonata on a Father Willis organ…! No. 3 also got a bit of TLC with Professor Higgs at Eastman during the first year of my MMus. This left the second, fifth, and first sonatas. I decided to learn the remaining two movements of No. 2 as I whiled away the hours of Lockdown #1 in Peterborough and later in Colchester (many thanks go to those who allowed me access to the Walker organ at St Leonard-at-the-Hythe), and I managed to finally learn No. 5 and No. 1 here in Evanston over the past couple of months.

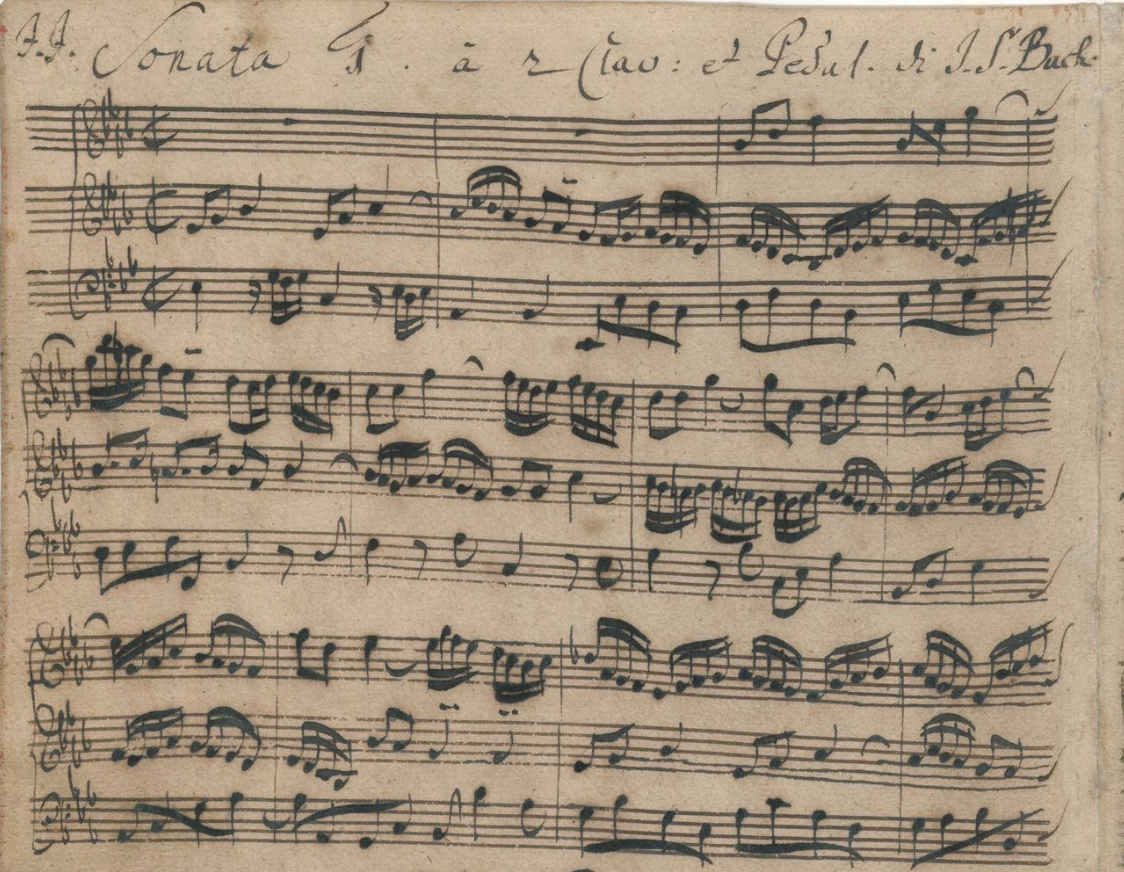

The opening of Bach’s first Trio Sonata, as notated in his hand in P 271 (see the Bach Digital Archive for more)